Letters of Commendation - A Biblical Example of Ecclesial Fellowship

In our day and age, recommendations are a very effective tool for an employer or admission office to assess the qualities of an applicant. Modern conveniences like the social networking site LinkedIn make commendations a key part of your profile. They add validity to a person’s trustworthiness and true capabilities.

The concept is not new. The Greeks and Romans wrote letters of commendation for many practical matters. Their style was part of the culture of New Testament times and would become part of the fabric of the early ecclesia. In fact, as we uncover Biblical examples it may surprise the reader as to the frequent use of letters of commendation, especially by the Apostle Paul.

It is important to recognize their use by the early ecclesia for two reasons. First, in a personal sense, it affects how we perceive ourselves, our humility, and how we put ourselves forward in service. Secondly, pertaining to the ecclesia, it demonstrates an attitude and carefulness in inter-ecclesial relationships, which we would be wise to follow.

First Century Practice

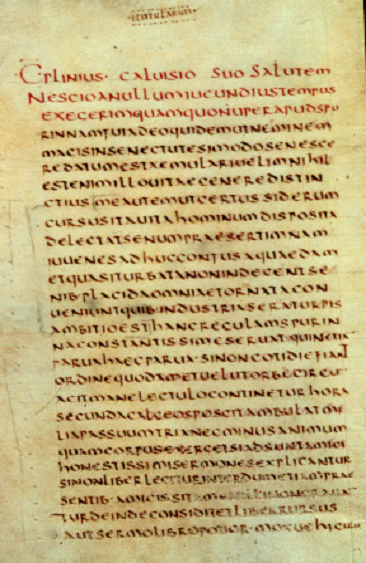

The elite leaders and socially important people commonly wrote letters of commendation in Greek and Roman times. There is a vast amount of examples left behind especially by such Roman luminaries as Cicero (106-43 b.c.e.), Pliny (61-120 c.e.), and Fronto (100-166 c.e.). These letters show a system of patronage for clients that they would wish to promote prominence places and thus establish their own position of authority. It was an exchange of power between those already in power and thus established the ruling classes of Roman order.

A good example comes from a letter of Pliny to the Emperor Trajan,

"Your generosity to me, Sir, was the occasion of uniting me to Rosianus Geminus, by the strongest ties; for he was my quaestor[1] when I was consul. His behaviour to me during the continuance of our offices was highly respectful, and he has treated me ever since with so peculiar a regard that, besides the many obligations I owe him upon a public account, I am indebted to him for the strongest pledges of private friendship. I entreat you, then, to comply with my request for the advancement of one whom (if my recommendation has any weight) you will even distinguish with your particular favour; and whatever trust you shall repose in him, he will endeavour to show himself still deserving of an higher. But I am the more sparing in my praises of him, being persuaded his integrity, his probity, and his vigilance are well known to you, not only from those high posts which he has exercised in Rome within your immediate inspection, but from his behaviour when he served under you in the army. One thing, however, my affection for him inclines me to think, I have not yet sufficiently done; and therefore, Sir, I repeat my entreaties that you will give me the pleasure, as early as possible, of rejoicing in the advancement of my quaestor, or, in other words, of receiving an addition to my own honours, in the person of my friend."[2]

The letter shows a genuine friendship between Pliny and Geminus, but it was one built on a patron-client relationship. Pliny was the benefactor for the advancement of Geminus into higher positions in Roman office and society. Without these types of "connections" nobody could receive advancement. At the end of the letter, Pliny is quite clear that he is not only looking out for Geminus but for his own welfare and status when he says, "receiving an addition to my own honours." Thus, these letters were self-serving in solidifying the power of those in authority.

This method of Roman patronage was so well exploited that even Jesus comments on it in Luke 22:25-26,

"And he said unto them, The kings of the Gentiles exercise lordship over them; and they that exercise authority upon them are called benefactors. But ye shall not be so: but he that is greatest among you, let him be as the younger; and he that is chief, as he that doth serve."

While the letters of commendation in the New Testament follow the same structure as Roman society, they could not have had more opposite intentions.

New Testament Word Studies

The letters of commendation embedded into the New Testament become apparent after a few word studies. The main word is "commend" but other words like "send" and "receive" also play an important part in identifying key passages.

Commend

Strong's Concordance yields a variety of Greek words for the subject of commendation.

- 4921 sunistano – to set together, by implication to introduce (Rom. 16:1; 2 Cor. 3:1; 4:2; 5:12; 6:4 “approving”; 10:12,18; 12:11)

- 1867 epaineo / 1868 epainos – to praise (Luke 16:8 “commended”; 2 Cor. 8:18)

- 3860 paradidomi – to give or deliver over (Acts 14:26 “recommended”; 15:40)

- 3908 paratithemi – to put near, to place with someone, entrust, commit, set before (Acts 14:23; 20:32; “commit” 1 Tim. 1:18 --> 2 Tim. 2:2 "commit")

- 3936 paristemi – to place near, set before, present, stand by, brought before (1 Cor. 8:8, “commendeth”, Romans 16:2 “assist”).[3]

- 1381 dokimazo / 1384 dokimos – approval after distinguishing and discerning[4] (1 Cor. 16:3; 1 Tim. 3:10; Rom. 14:18; 2 Cor. 10:18).

Taking all these words together, commendation was the act of setting someone in front of another to introduce and praise them. In many cases there was an ability or office involved where the person was entrusted with a responsibility. Care would be exercised that the one being commended would be trustworthy and stable. This is why the letters of commendation often use the word "approve" (1381 dokimazo / 1384 dokimos).

Send and Receive

The act of commending someone by a letter involved "sending" the person on some sort of errand or mission and expecting the other party to "receive" or welcome that person for the work they were to do. In a day without telephones and email, the letter would be the key means that a person was genuine and could be trusted. Not only did it protect against fraud but also ensured that the person could not boast of themselves more than they were.

There are two main Greek words used for "send" in the New Testament: pempo and apostello.[5]

- 3992 pempo – to dispatch (Acts 15:22, 25; 1 Cor. 16:3; 2 Cor. 9:3; Eph. 6:22; Col. 4:8; Phil. 2:19, 23, 25, 28; 1 Thess. 3:2; Tit. 3:12). A number of root words are,

- 375 anapempo (Philemon 1:12),

- 1599 ekpempo (Acts 13:4),

- 4842 sunpempo – to send along with (2 Cor. 8:18, 22) and

- 4311 propempo – to send forward, escort, conduct forth (Acts 15:3).

- 649 apostello – to send forth on service or with a commission (Acts 15:27; 19:22; 2 Cor. 12:17-18; 2 Tim. 4:12).

Similarly, there are two words for "receive": dechomai and lambano.

- 1209 dechomai – accept, receive, take (Matt. 10:39-42; Acts 21:17; 2 Cor. 7:15; Col. 4:10). Root words include:

- 588 apodechomai – to take fully, i.e. welcome, approve, accept, receive gladly (Acts 15:4; 18:27),

- 4237 prosdechomai – to admit, accept, allow, by implication to await (Rom. 16:2; Phil 2:29),

- 1926 epidechomai – to admit, receive (3 John 9-10).

- 2983 lambano – to take, to get hold of (2 John 1:10). Root words are:

- 4355 proslambano (Acts 28:2; Rom. 14:1, 3; 15:7; Phm. 1:12,15-17),

- 618 apolambano – to receive in full or as a host (3 John 8)

Jesus emphasizes the concept and importance of these words by repetition in Matthew 10:14-16, 40-41.

"Behold I send you forth (v.10) .... whoseover does not receive you... shake of the dust of your feet (v. 14) ... he that receiveth you receiveth me, and he that receiveth me reciveth him that sent me."

Form and Structure of Commendation Letters

The structure of a passage also provides clues. When I was in school, we learned about letter writing and their different forms. This seemed to be the case in Roman society as well. All of the letters of commendation from Cicero, Pliny and Fronto had a similar style and structure. The following summarizes the key points:

- Identify the one being commended

- Cite the criteria and credentials for commendation

- Make a request of the letter’s recipient

This structure will show up repeatedly in the letters of Paul and will help us to recognize his letters of commendation.

The New Testament Examples

At this point, we can come up with a rather long list of actual letters of commendation or ones appended to epistles.

- Paul, Barnabas, Judas and Silas (Acts 15:22, 25-27)

- Phoebe (Rom. 16:1-2)

- Stephanus, Fortunatus and Achaicus (1 Cor. 16:15-18)

- Envoys for poor fund (2 Cor. 8:16-24)

- Tychicus (Eph. 6:21-22; Col. 4:7-8)

- Onesimus and Marcus (Col. 4:7-10)

- Timothy (Phil. 2:19-24; 1 Cor. 4:17; 16:10-11; 1 Thess. 3:2)

- Epaphroditus (Phil. 2:25-30)

- Euodia and Syntyche (Phil. 4:2-3)

- Leaders (1 Thess. 5:12-13)

- Philemon (in full)

Moreover, we can also compile a list where we do not have the actual recommendation but we have mention of its practice.

- Paul and Barnabas sent and recommended by the Antioch ecclesia and the Holy Spirit (Acts 13:3-4, 14:26)

- Paul and Barnabas as envoys of the Antioch ecclesia to the Jerusalem conference (Acts 15:2-4)

- Apollos (Acts 18:27)

- Those sent to take the money for the Jerusalem poor fund (1 Cor. 16:3)

- Missionaries (1 John 3)

It may be surprising to find that this subject touches on much of the New Testament. While we would encourage the reader to look up every example as a worthy exercise, we will only comment on a couple of specific examples.

The Jerusalem Conference

The first example occurs in the incidents surrounding the Jerusalem Conference in Acts 15. The debate had started in Antioch that "except ye be circumcised after the manner of Moses, ye cannot be saved" (v. 1). The dispute was so great that "they" (v. 2), that is, the Antioch ecclesia, decided to send representatives, Paul and Barnabas, to the apostles and elders in Jerusalem to decide the final resolution. One of our key words comes in verse 3,

"And being brought on their way by the church..." (KJV)

The Greek word for "brought" here is propempo and all modern translation use the word "sent". Therefore, Paul and Barnabas did not go of their own accord but were sent by the Antioch ecclesia. As we have already seen, this word implies a recommendation by the sending party especially when paired with the act of "receiving", which we have in verse 4.

"And when they were come to Jerusalem, they were received of the church, and of the apostles and elders, and they declared all things that God had done with them."

We should not take the manner of this as a casual exchange. There is an intentional "sending" and "receiving" being done. There is no mention of a letter but we can assume with some confidence that there was one. There is no assumption that Paul and Barnabas could be representatives of their own accord. The Antioch ecclesia[6] granted them that position and the Jerusalem ecclesia welcomed them on that basis.

The order of the words in verse 4 is interesting as they are received first by the church and secondly by the apostles and elders. It is interesting because the order is reversed in verse 22.

"Then pleased it the apostles and elders, with the whole church, to send chosen men of their own company to Antioch with Paul and Barnabas; namely, Judas surnamed Barsabas, and Silas, chief men among the brethren"

It was only the "apostles and elders" (v. 6) who came together to consider the matter but in the end the decision "pleased" the whole ecclesia. That is, they were not left out of the decision process and approved to "send" (pempo) their own representatives back to Antioch. The letter they[7] composed was therefore a declaration of their decision but also a letter of recommendation for those who carried it.

(Act 15:25-27) "It seemed good unto us, being assembled with one accord, to send (pempo) chosen men unto you with our beloved Barnabas and Paul, (26) Men that have hazarded their lives for the name of our Lord Jesus Christ. (27) We have sent (apostello) therefore Judas and Silas, who shall also tell you the same things by mouth."

Apollos

We are introduced to Apollos in Acts 18:24 where we learn that he is a Jew, mighty in the scriptures and preached the things of the Lord only knowing the baptism of John. It seems he was a traveller having come from Alexandria in Egypt all the way to Ephesus and had the intent to spread the word in other places. Once Aquila and Priscilla had instructed him more perfectly in the way of God they encouraged him to go to other areas and preach but not before writing a letter of recommendation.

(Act 18:27) "And when he was disposed to pass into Achaia, the brethren wrote, exhorting the disciples to receive (apodechomai) him: who, when he was come, helped them much which had believed through grace."

One wonders how Apollos would have fared without this letter in hand? It seems an ecclesia would not receive a travelling stranger without a recommendation even though he might confess to believe the same things. Aquila and Priscilla followed practical measures that would allow Apollos’ acceptance into fellowship with open arms wherever he went among the established ecclesias.

Phoebe

A great example of a letter of commendation is Romans 16:1-2 where Paul commends Phoebe to the ecclesia in Rome.

"I commend unto you Phebe our sister, which is a servant of the church which is at Cenchrea: (2) That ye receive her in the Lord, as becometh saints, and that ye assist her in whatsoever business she hath need of you: for she hath been a succourer of many, and of myself also."

This follows the typical form and structure of the period’s letters of commendation. It is fair to assume that the Apostle sent Phoebe who personally delivered the whole epistle to the ecclesia in Rome. This sending and commendation of Phoebe may have been Paul's original task of which he decided to write a lengthy dissertation in front of the letter of commendation.

She comes highly qualified in glowing terms yet Paul still urges them to "receive her in the Lord, as becometh saints". The qualifying phrase "in the Lord" (seen also in Phil. 2:29 and Phil. 15-17) indicates that it had to do with welcoming somebody into fellowship.[8] This was something reserved or worthy of only the saints.

The Jerusalem Poor Fund

Much of the epistles to the Corinthians involve a collection made by the Gentile ecclesias to support the poor brethren suffering through a famine in Jerusalem. In matters involving money there would have to be an extreme sensitivity that those bearing the funds would be trustworthy and beyond reproach. Paul left this decision up to the Corinthians.

"And when I come, whomsoever ye shall approve by your letters, them will I send to bring your liberality (mg. gift) unto Jerusalem."

It was not enough just to pick some nice brethren to do the job. Paul expected them to write a letter of recommendation so that he could in all good conscious "send" them for the work. Paul gives his reasoning for doing this in 2 Cor. 8:20-21 (ESV),

"We take this course so that no one should blame us about this generous gift that is being administered by us, (21) for we aim at what is honorable not only in the Lord's sight but also in the sight of man."

In this context, Paul writes a highly complementary recommendation for those doing the work and is very careful to show that this was not of his initiative but was a recommendation by the ecclesias. That the ones he was "sending" (v. 18, 22) where "chosen" (v. 19) by the ecclesias and therefore were "messengers (apostles - ones sent) by the church" (v. 23).

Paul's Letter of Commendation to Philemon

While many of the New Testament epistles have embedded letters of commendation (e.g. Timothy and Epaphroditus in Phil. 2:19-30) the epistle to Philemon stands alone as a letter of commendation in whole. The story goes that Onesimus, a servant of Philemon, runs away and eventually is converted by Paul in Rome. Paul instructs Onesimus to go back to his master with this letter in hand. Onesimus as a runaway slave faces certain punishment but Paul uses the method of writing a letter of commendation in standard form and function for Roman society to persuade Philemon not to do this but to receive Onesimus as a brother in the Lord.

While the word "commendation" is not used, the nature of the letter is apparent by the loving terms Paul uses for Onesimus and his use of the key words "send" and "receive".

(Phm 1:12) "Whom I have sent again: thou therefore receive him, that is, mine own bowels."

(Phm 1:15-17) "For perhaps he therefore departed for a season, that thou shouldest receive him for ever; (16) Not now as a servant, but above a servant, a brother beloved, specially to me, but how much more unto thee, both in the flesh, and in the Lord? (17) If thou count me therefore a partner, receive him as myself."

Paul implored Philemon to receive him back. Not just as a servant in bonds, but much more, as a brother in Christ. The receiving had to do with fellowship in the Lord. The special nature of the case has ensured its preservation in our Bibles, but it makes one wonder how many other letters of recommendation were written among the ecclesias of the time? There can be no doubt that it was standard practice.

3 John

The apostle John hints at his use of letters of commendation for travelling brethren (verse 3) that had come back to him with a report of those who were walking in the truth. With a careful reading of 3 John we can safely assume that John sent these brethren on a mission with a letter of commendation because they would be unknown to the other ecclesias. The letters would then ensure ample support and help by the local ecclesias for the work they were doing. John thanks them for their service and generosity in verses 5-6,

(3 Jn 1:5-8) "Beloved, thou doest faithfully whatsoever thou doest to the brethren, and to strangers; (6) Which have borne witness of thy charity before the church: whom if thou bring forward (propempo) on their journey after a godly sort, thou shalt do well: (7) Because that for his name's sake they went forth, taking nothing of the Gentiles. (8) We therefore ought to receive (apolambano) such, that we might be fellowhelpers to the truth."

The King James translation of verse 5 reads as if there are two classes “the brethren, and to strangers” but it should read more like the ESV, “for these brothers, strangers as they are…” They might have been strangers at first but as soon as they would have read the letter of commendation, they would have quickly bonded in the truth and been welcomed.

Our keywords "send" and "receive", used in these verses, indicates the practice of commendation. John encourages the ecclesia to "bring forward" such missionaries, which most modern translation have as the word "send". For instance the NKJV reads, "If you send them forward on their journey in a manner worthy of God, you will do well." This is paired, as we have seen now so often, with the aspect of "receiving" in verse 8, which is all centered on the aspect of proper fellowship practice so that we might be "fellowhelpers to the truth."

To not "receive" someone who had been "sent" was a serious matter that spoke not only against the travelling missionaries but also against the one who had sent them in the first place. This was Diotrephes.

(3 Jn 1:9) "I wrote unto the church: but Diotrephes, who loveth to have the preeminence among them, receiveth (epidechomai) us not."

John says at the beginning of verse 9 that he "wrote unto the church." What letter is John referring to here? Based on the context, this was most likely the letter of commendation John had sent with the brethren, which Diotrephes had rejected. We can imply this as well when John says that Diotrophes "receiveth us not" (v. 9) and that "neither doth he himself receive the brethren" (v. 10).

John took the rejection of his commendation very personally when he says Diotrophes “receiveth us not” (v. 9). This follows the principle, so often in scripture, that he who receives you, receives me and he who rejects the one sent, rejects the one who sent (Matt. 10:40-41; 18:5; Luke 10:16; John 13:20). Therefore, Diotrephes’ rejection of John's commendation of these travelling brethren was truly a rejection of the apostle John himself.

Practical Implications for Our Day

The apostolic and ecclesial practice of commendation is a guide for our personal and inter-ecclesial conduct. Personally, it shows forth a spirit of humility and not wanting to boast. Secondly, it shows an ecclesial carefulness to ensure proper fellowship.

Self-Commendation

Paul had a problem with the Corinthians who were questioning his motives and qualifications. It upset Paul so much that these brethren and sisters whom he knew so well were treating him as some sort of stranger. In an exasperated tone he says to them in 2 Corinthians 3:1,

“Do we begin again to commend ourselves? or need we, as some others, epistles of commendation to you, or letters of commendation from you?”

At once, the practice of letters of commendation jumps out, but in this case, it would be needless for such a letter. Paul bemoaned the fact that he had to boast about his own qualifications to those who knew him. Yet throughout the epistle, he battles and succumbs to “commending” himself.

(2 Cor 4:2) “… by manifestation of the truth commending ourselves to every man's conscience in the sight of God.”

(2 Cor 5:12) “For we commend not ourselves again unto you, but give you occasion to glory on our behalf, that ye may have somewhat to answer them which glory in appearance, and not in heart.”

(2 Cor 6:4) “But in all things approving ourselves as the ministers of God, in much patience, in afflictions, in necessities, in distresses…”

(2 Cor 10:12) “For we dare not make ourselves of the number, or compare ourselves with some that commend themselves: but they measuring themselves by themselves, and comparing themselves among themselves, are not wise.”

(2 Cor 10:17-18) “But he that glorieth, let him glory in the Lord. (18) For not he that commendeth himself is approved, but whom the Lord commendeth.”

(2 Cor 12:11) “I am become a fool in glorying; ye have compelled me: for I ought to have been commended of you: for in nothing am I behind the very chiefest apostles, though I be nothing.”

Paul had felt compelled to become foolish in defending himself to the Corinthians. Having to qualify ourselves should not be a comfortable position for any humble servant of Christ. Approval of who we are and what we stand for is best coming from others. Paul always looked for approval from the ecclesia. This is a model for us to follow, that when we travel and visit other ecclesias we should be taking with us the commendation of our ecclesia. If we do not have that, then looking to be “received” into fellowship is questionable.

Approval of Men

Certain brethren and sisters may chaff at the thought of seeking approval from men. There is no doubt that a Pharisaic attitude could arise where we seek the praise of men rather than the praise of God (Matt. 6:1; 23:5; John 12:43; Acts 5:29; 2 Thes. 2:4) but the scriptures are also clear that it is not always a bad thing if the motives are correct. In fact, it is better for us to seek praise from others rather than ourselves as it says in Proverbs 27:2,

“Let another man praise thee, and not thine own mouth; a stranger, and not thine own lips.”

The spontaneous approval of men that naturally arises out of the recognition of a good character is admirable. It is said of Jesus[9] “he grew in favour with God and man” (Luke 2:52). This he did by following the principles in Proverbs 3:3-4,

“Let not mercy and truth forsake thee: bind them about thy neck; write them upon the table of thine heart: (4) So shalt thou find favour and good understanding in the sight of God and man.”

Therefore, if we are a brother or sister, known of others to be standing fast in the Lord, then the praise of others is what really matters. It should not and does not need to come from ourselves. The approval of men then is not something to disregard for in the right context it is desirable. Paul shows this to be the case in Romans 14:18,

“For he that in these things serveth Christ is acceptable to God, and approved of men.” (see also 2 Cor. 8:21; Acts 2:47)

Inter-Ecclesial Fellowship

The responsibility of an ecclesia is to watch over and encourage the spiritual development of its own members. In a healthy environment, the shepherds of the ecclesia know the attitudes and standing of those in the ecclesia. They are the ones best fit to provide a true assessment of a brother or sister’s character. It would seem right then that ecclesias would still seek to affirm and encourage the practice of commendation both of those who are “sent” and “received”.

Similarly, the ecclesia must make decisions on whom to receive into fellowship. Did any first century ecclesia accept anybody without a letter of recommendation? Even if the visiting brother commended himself, would fellowship be offered and left to his conscious? We have no commandment given to the ecclesias but with so many examples given it would seem reasonable that the answer in practice is “no”.

In terms of fellowship, Bro. Thomas wrote in 1869,

“Declare what you as a body believe to be the apostles doctrines. Invite fellowship on that basis alone. If any take the bread and wine, not being offered by you, they do so on their own responsibility, not yours.”[10]

While this might seem at first to be reasonable, it does not correlate with what we have just seen as the ecclesial practice of recommendation before a person’s reception into fellowship. Leaving the decision of breaking bread and wine solely in the hands of a visitor is to abdicate a responsibility of the ecclesia.

From the earliest years of the Christadelphians, there has been recognition of the need to write letters of commendation when transferring membership from one ecclesia to another. Examples fill the intelligence section of the magazine. Sometimes the lack of such a letter created problems as is apparent in this notice from 1872,

“Brethren Removing from one place to another .—Such should always provide themselves with a letter of recommendation from the ecclesia with which they have been assembling. There have recently been several instances of awkwardness from want of the necessary introduction.”[11]

Even in terms of visitation, some ecclesias adopted a rule,

“Chicago , Ill.—Brother W A. Harris says “We have thought it necessary to adopt the rule adopted in England and elsewhere, that when a stranger visits us, he be required to produce a letter of recommendation before we receive him into our fellowship; failing which, we appoint a committee to confer with him as to the identity of his faith and practice with ours.”[12]

While these brethren state it as a rule, they nevertheless are basing it off sound scriptural principles.

This became the norm throughout the Central Christadelphian brotherhood. As the number of ecclesias grew, the practice developed into acceptance of anybody in good standing from a Central ecclesia. The article in The Christadelphian Magazine of 1995 puts it succinctly,

“The fact that fellowship arises from ecclesial membership allows the ecclesial world to be travelled without difficulty. By presenting himself as a member in good standing of a Christadelphian ecclesia in the central fellowship, a brother will be invited without further question to share in the fellowship of the Lord’s table with his brethren and sisters. Any other arrangement would be unworkable, of course. It would be impossible to undertake an enquiry into every visitor’s beliefs on the door-step of the ecclesial hall, but this would prove necessary if there were no safeguard such as is provided by a brother or sister’s membership of an ecclesia. Thus it is the ecclesia, and not the individual, who is the arbiter of his or her fellowship standing, and it is their home ecclesia’s assessment which is taken into account when individual brethren and sisters visit ecclesias where they are not personally known.”[13]

Conclusion

Influenced by the culture of the times, the first century ecclesia adopted letters of commendation in its own unique way for the protection of fellowship among the ecclesias. As we have seen, the practice is woven throughout the fabric of the New Testament. As modern day ecclesias in the Lord, we would like to say that we emulate similar procedures.

This is not as a rule but as a wise practical matter. We have seen the expectation and usage of commendation among ecclesia is the best method we have a preserving the truth in these last days. True fellowship in the Lord is a serious matter given to the ecclesias to implement.

Furthermore, we consider ourselves, lest any man should boast of himself. The practice of commendation mitigates self-commendation and establishes Godly humility. It makes one realize the acceptance into fellowship is not a right but a privilege.

If we do these things, Lord willing, before the judgment seat we will be given the greatest commendation of all, even to be presented “faultless before the presence of his glory with exceeding joy” (Jude 1:24).

[1] A quaestor was any type of official who had charge of public revenue and expenditure.

[3] This word is also used in presenting before the judgment seat (2 Cor. 4:14; 11:2; Eph. 5:27; Col. 1:22,28; Rom. 14:10 “stand before”)

[4] See Vine's Dictionary entry on "Approve, Approved "

[5] Vine's Dictionary entry on "sent" has more information on the differences between pempo and apostello.

[6] For an earlier example of the Antioch ecclesia commending Paul and Barnabas compare Acts 13:3 with 14:26.

[7] Notice the letter is written by "the apostles and elders and brethren" indicating that the ecclesia was also included in the formal formation of the words sent to all the ecclesias.

[8] The word "receive" is used earlier in Romans 14:1 and 15:7 in aspect of fellowship.

[9] And Samuel (1 Sam. 2:26)

[10] Reproduced in The Christadelphian, 1873, pg. 323

[11]Vol. 9: The Christadelphian : Volume 9. 2001, c1872. The Christadelphian, volume 9. (electronic ed.). Logos Library System (Vol. 9, Page 614). Birmingham: Christadelphian Magazine & Publishing Association.

[12]. Vol. 10: The Christadelphian : Volume 10. 2001, c1873. The Christadelphian, volume 10. (electronic ed.). Logos Library System (Vol. 10, Page 47). Birmingham: Christadelphian Magazine & Publishing Association.

[13]. Vol. 132: The Christadelphian : Volume 132. 2001, c1995. The Christadelphian, volume 132. (electronic ed.). Logos Library System (Vol. 132, Page 386). Birmingham: Christadelphian Magazine & Publishing Association.